TaleSpire Dev Log 127

Recently I’ve been spending most of my time working on undo/redo support and general data model work inside TaleSpire. Because of that, I thought I’d take a post to ramble a little about undo/redo and how a ‘simple’ feature can grow when you have a few constraints.

This is not the exact way we are doing things in TaleSpire, but it’s an exploration of an idea I went through whilst looking at the feature.

In this post, I’m only going to talk about placing/deleting tiles rather than creatures to keep things simpler.

Chapter 1 - Building basics

So lets first have a look at a little building:

Players can do a few things:

- They can place a single tile

- They can drag to place multiple tiles

- They can delete a single tile

- They can select and then delete multiple tiles

- They can copy and paste slabs of tiles

We are going to refer to placing tiles as an add operation and deleting tiles as a delete operation

There is no moving of tiles in TaleSpire, anything that looks like a move is actually a delete operation followed by an add operation. So cut and paste work like this. However, for now, we will ignore copy/paste and just look at the fundamental operations.

What can we say we know about add operations:

- The building tools should ensure that the new tile/s do not intersect any existing geometry

- The building tools should ensure that no two tiles in a drag

addoperation intersect.

For now, we will just leave these points here but we will refer back to them later. One thing of note though is that the ‘does not intersect’ property is something we want to try and maintain. Due to undo/redo it’s pretty easy for people to violate this[0] but the rest of the system should try to maintain this as much as possible.

All right, so our building tools let the player add and delete tiles, but we have to maintain this state in memory. Our world (the board in TaleSpire) can be far too big to fit in memory all at once so we divide the world up into zones which we can load in and out on demand. Because of this, we will want zones to be as independent as possible and so each zone is going to maintain it’s own tile data.

An add or delete of a single tile seems like a simple place to start, it should only affect one zone right? Well, it depends on the size of the tile. Let’s say our zones are 16x16x16 units in size and that the minimum size of a tile is 1x0.25x1 (where the 0.25 is the vertical component), well then if a single tile is 40x1x40 then it could be overlapping nine different zones. Even a humble 2x2x2 tile can overlap eight zones if it is in the corner. For the sake of sanity let us say that a tile can be no bigger than half the size of the zone (8x8x8), this way it can at most overlap eight zones, just like the 2x2x2 tile. We will also leave this issue here for now as we will have enough to think about, however, keep in mind how many little things we are ignoring for the sake of the readability of the article, all of these will need to be resolved before your game ships :p

Back to adding tiles! When tiles are placed we need to store data about them, things like the kind of tile it is, the position, rotation, etc. We will just talk about a tile’s data as if it’s a single thing for simplicity[1].

First player0 drags out 3 tiles.

tile-data = [add(* * *)]

tile-data is some linear collection holding the tile data and add is an object holding three tiles represented by asterisks (*) in this case.

Ok so they add 2 more tiles

tile-data = [add(* * *), add(* *)]

Neat. Now let’s look at undo. Well, that’s pretty simple right now as we have been storing our tiles in the order they happened, let’s just drop that most recent add.

tile-data = [add(* * *)]

Hmm, but now we need to support redo, it’s a shame we just threw away the data on the undo. What if we didn’t, what if we had a little store of things that have been ‘undone’. That means after the undo the data would look like this

tile-data = [add(* * *)]

undone-data = [add(* *)]

and now redo is simple too. We pop the data off of the undone-data stack and push it back onto tile-data.

tile-data = [add(* * *), add(* *)]

undone-data = []

So far so groovy. But now let’s think about deleting tiles. Well, that doesn’t map to our data layout as neatly. Our tile data is organized in chunks that are ordered by when they happened in history, not by where they are in the world. Our zones do offer a limited amount of subdivision of the world so currently, this means we need to visit each zone the selection intersects and then scanning through all the tiles in those zones to see which are in the selection. [2]

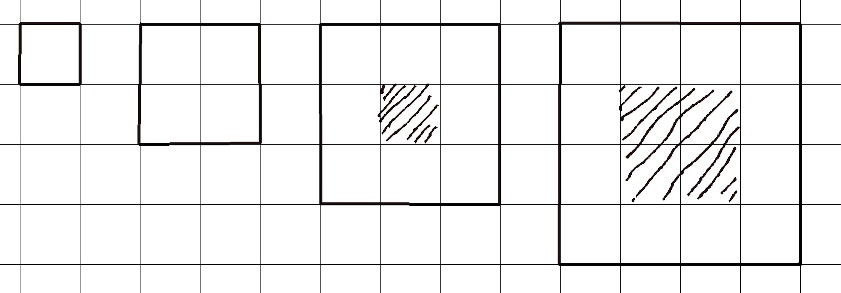

So about those zones.. how many are going to be involved? Let’s look at this 2d version.

Notice how, as the size increases the number of zones we need to consider is going up by the width x height and it’s more painful in 3D as it’s increasing by width x height x depth, so roughly cubing with respect to edge length. This is going to be quite a lot of zones to check. But how many tiles can a zone hold? Well a zone is 16x16x16 but a tile can be as small as 1x0.25x1 then that is 16x64x16 tiles 16384tiles…ugh this is getting to be a lot of work.

But a ray of hope appears, notice the hatched areas in the diagram above. Those are zones that are completely enclosed by the selection. Naturally, this means a delete operation will delete all the tiles within so we have an opportunity for a big optimization. For any zone that is completely enclosed we just remove all tiles, and we only compare the selection with the tiles themselves for zones that are only partially intersected by the selection. In general, this means the outer ‘surface’ of zones. The number of zones on the surface of the selection grows roughly in the order of (x^3 - max(x-2, 0)^3) which is much more manageable.

The situation has improved then but we still need to apply the operation to all those zones, and quickly. Luckily you have been watching the recent developments in your game engine of choice and have learned that they have added a neat job system which can spread work over multiple cores and has a specialized compiler which can optimize the heck out of your code. “Yay” you say, but one limitation all your data need to be Blittable types or arrays of such so our previous ‘list of chunks of tiles’ approach isn’t going to work. Furthermore, it would be neat if the tile data was packed together in memory so you could write that jobs that traverse the whole set of tiles rather than jumping around memory to separate chunks. This becomes important as you watch your players and notice that, whilst they do drag out large chunks of tiles, they also place a lot of tiles one at a time.

Ok so let’s look at our old data layout

tile-data = [add(* * *), add(* *)]

undone-data = []

Now let’s make this a single array, and instead of undo removing one and adding to another we with have an index which we will call the active-head. It will point to the most recent active chunk of tiles

v

tile-data = [add(* * *), add(* *)]

Our active-head is represented by the v above tile-data in code it’ll just be an integer.

With that change undo looks like this

v

tile-data = [add(* * *), add(* *)]

and redo does this

v

tile-data = [add(* * *), add(* *)]

Cool, but now to remove those extra objects, let’s flatten the array and move the layout information to a separate array

v

tile-data = [* * * * *]

v

layout = [3 2]

So far so good. Now our layout tells us how many tiles are in each chunk and tile-data stores all the tiles packed together.

Undo now looks like this…

v

tile-data = [* * * * *]

v

layout = [3 2]

and redo is still the reverse. This means undo and redo are still as simple as changing an integer from the data-model side[3]

Delete is different though, delete is based on a region on the board so we need to check each tile to see if it intersects with that region and, if it does, then we remove it from the tile-data array. Undo naturally requires us to put that data back. Now from a data angle that is annoying as it could leave ‘holes’ in our array as in the following diagram (deleted tiles represented by x)

v

tile-data = [x * x x *]

v

layout = [3 2]

This is no good as now we have to handle this. We could have each tile have a flag that says if it’s alive or dead. We would then need to check that any time we scan over this array. This is ok but, unless we undo the delete, we still have memory being wasted as it’s occupied by data for tile that been deleted. So maybe we reuse the gaps? Sounds great, but we can’t fill in the gaps with tiles from newer operations as otherwise, we lose the property that tile-data is in ‘history order’ and thus lose the ability for undo/redo to be represented by the active-head.

So if we don’t want holes but can’t fill them then another option is to compact the array as we delete, so whenever tile data is deleted the tile data to the right is shifted left to fill in the gaps. This requires more copying during the delete but let’s assume we profiled it and it proved to be the best option[4]. This is what we will assume for the rest of the article.

Let’s now look at the above delete operation with compaction.

v

tile-data = [* *]

v

layout = [1 1]

Neat! but we should note we have complicated undo for ourselves. If we undo a delete We will have to ‘make room’ in tile-data for the old tiles to be copied back into. There is one blessing though, we only care that chunks are in history order, not the tiles within the chunks. That means we don’t need to make room in the same places as we had the tiles originally…

v

tile-data = [_ * _ _ *]

v

layout = [3 2]

Rather, we can make room at the end of each chunk…

v

tile-data = [* _ _ * _]

v

layout = [3 2]

And still keep all the undo/redo benefits we had previously with the active-head approach.

This also simplifies redo of a delete, can you spot how?

Originally we had to scan through the tiles to find the ones to delete. Redo requires us to delete those same tiles again but we know exactly where they are now, they are at the end of each chunk.

Chapter 2 - Multiple players and a quandary

Now things get ‘fun’. We can have up to 16 players on a board at a single time and all of them could be given the permissions to build. That means we need to keep that all in sync on all machines but all make sure everything feels instant.

Let’s get one thing out of the way quickly, order matters. By this I mean the obvious quality that an add followed by a delete can give a different result from a delete followed by an add, from this we know we need to apply changes in a fixed order. For us, that means when we build we will send a request to a ‘host’ which will decide what gets applied in what order and tells the other player’s games (called a client from now on). Note that we also need to see a change the moment it happens so the order will be:

- Player tries to make a change

- The local client applies the change immediately and sends a change request to the host

- the local client listens for change acknowledgments from the host

- if the acknowledgement is for the thing we just built then we are done

- if the acknowledgement is for another client’s change then we undo our change, apply their change and then reapply our change

Now that is very briefly covered we will assume that things are applied in the same order on each client and ignore that aspect of the problem for the rest of the article.

To keep everything in sync we need to be able to send information about what is being done by each player. We already know that our selections could be very large so we don’t want to have to send information about every specific tile that was modified, so instead we will want to send just what happened e.g. ‘player 0 added 30 wall tiles in this area’. This is ok for us as we are already assuming a fixes order of operations so we can assume that every player has the board in the same state when they apply the change.

Multiple players building also gets interesting due to each player has their own undo/redo history. This is very important as shared histories get very annoying very quickly. However, this messes with our little data layout from before. In the following layout I have changed out the asterisks for a designation that tells us who added the tile, this is only for our benefit in this article, it needed to be encoded in the actual data like this.

v

tile-data = [p0 p0 p1 p1 p0 p0]

v

layout = [2 2 2]

So three chunks of tiles have been added. First player0 (p0) added 2 tiles, then player1 (p1) added 2 and then p1 added 2 more.

Now let’s say p1 hits undo, that means the middle two tiles need to be undone but we can’t do this just by shifting the active head.

Here we face two choices, either we drop the active-head approach or keep it and find a way around the above issue. Neither way is wrong and both require changes to how the data will be stored. For the sake of the article, I am just going to continue with the active head approach so we can see how this has to be modified to keep its nice properties in the face of multiple players.

Chapter 3 - Multiple Players with the active-head approach

OK, so let’s say we like the way we can just change a single integer to represent undo/redo using the active-head approach. What would be needed to keep this working with multiple players?

Well each player could have their own tile and layout data

v

p0-data = [p0 p0 p0 p0]

v

p0-layout = [2 2]

v

p1-data = [p0 p0]

v

p1-layout = [2]

This lets us regain the quality that undo for p1 only affects p1’s data.

From now on let us say that if a tile is in p0-data then player0 ‘owns’ that tile and if the tile is in p1-data then player1 ‘owns’ that tile. With that little bit of terminology, we can look at delete again.

Delete is based on a selection of tiles on the board, it does care about who ‘owns’ the tile behind the scenes; if the tile is in the selection, it will be deleted. That means that when we scan the data for tiles to delete we need to scan each player’s tile array.

Remember how undo of a delete needed to restore tiles to where they came from? Well, what do we do for tiles that we delete from other players? It turns out that adding them back to the other player’s chunks (and thus their history) results in behavior that is fairly confusing to play as the result of undo or redo depends to an extent on the current state of another player’s undo or redo. How robust a game feels depends a lot on to what degree a player’s expectations of game behavior match reality and so it’s sometimes better to have a simpler behavior even if a more correct but complicated option is available. I’m going to claim this is such a case without trying to prove it here :)

The result of this is that we don’t want to try to push undone deletes back into the data arrays of other players. So where do we put them? How about the end of our data section? This is a bad idea as is breaks the active-head approach again. So for us to continue using this approach we now need an additional store per player for undone deletes.

v

p0-data = [p0 p0 p0 p0]

v

p0-layout = [2 2]

p0-deletes = []

v

p1-data = [p0 p0]

v

p1-layout = [2]

p1-deletes

= []

The addition of more per player data probably feels annoying (it did to me) but one upside is that this array can use the same active-head tricks that we have used for the player’s data array but with a slight difference, the tiles exist in-game only if they are to the right of the active-head. In this case:

- a delete of tiles owned by other players pushes them onto the player’s

deletesarray and advances the active-head - an undo of the delete shifts the active-head to the left, the things to the right are now active in-game

- a redo of the delete shifts the active-head right again

Conclusion

This might feel like it’s all getting a bit out of hand. That is a fair conclusion to make! This is why I said at the beginning this writeup is just an exercise in following an idea through to where it leads rather than making a call on the best approach. I hope you have some thoughts on this and also a feeling for where this kind of feature can get complicated.

I have left out a bunch of things like “how do we maintain the mapping between the tile data my game engine’s game objects when our data can only contain Blittable types?” and “How long can undo/redo histories be?”. They are fun in themselves as I do recommend considering them if you decide to try and come up with your own schemes.

Notes

[0] For example imagine player0 placing a block of tiles, then player0 deletes those tiles, then player1 places some tiles in that (now empty) spot. Finally player0 undoes their delete and suddenly player1’s tiles intersect with player0’s.

[1] This means we are ignoring both the fields within and also the various possible layouts for those fields.

[2] We could of course store the ‘bounds’ (a 3d region) of the tiles organized in a way that makes spatial queries easier, and then have those contain indexes back to the tiles they refer to. This will mean sorting/maintaining this structure as tiles are added/deleted, so it’s not a free lunch but you will want to look at this if you are building this yourself.

[3] you still need to handle the relationship between the data and actual GameObjects or entities (depending on the system you are using)

[4] remember that building only happens as fast as humans can click, whereas some things might be happening every frame (60 times a second). It can prove better to prioritize the more common case over the less frequent one even if it does result in a slight drop in performance for the less common case.